Writer, Activist, Professor, Speaker

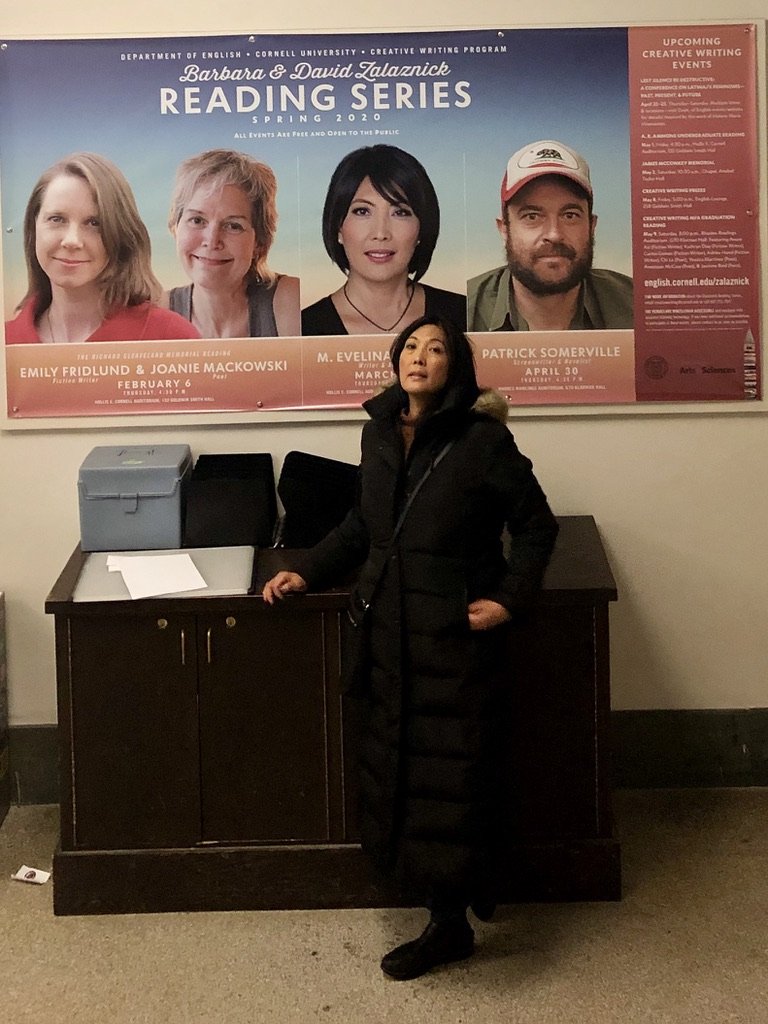

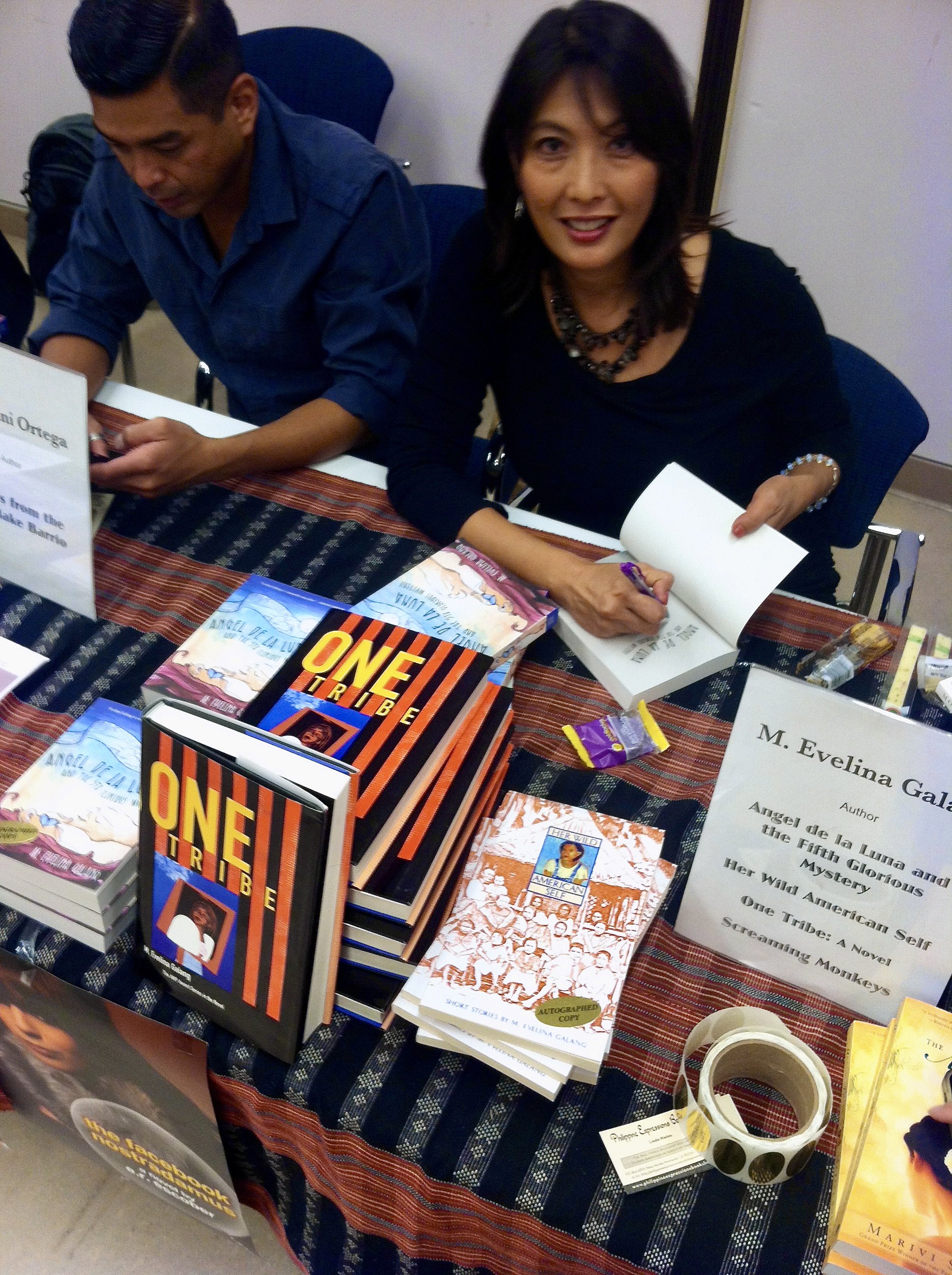

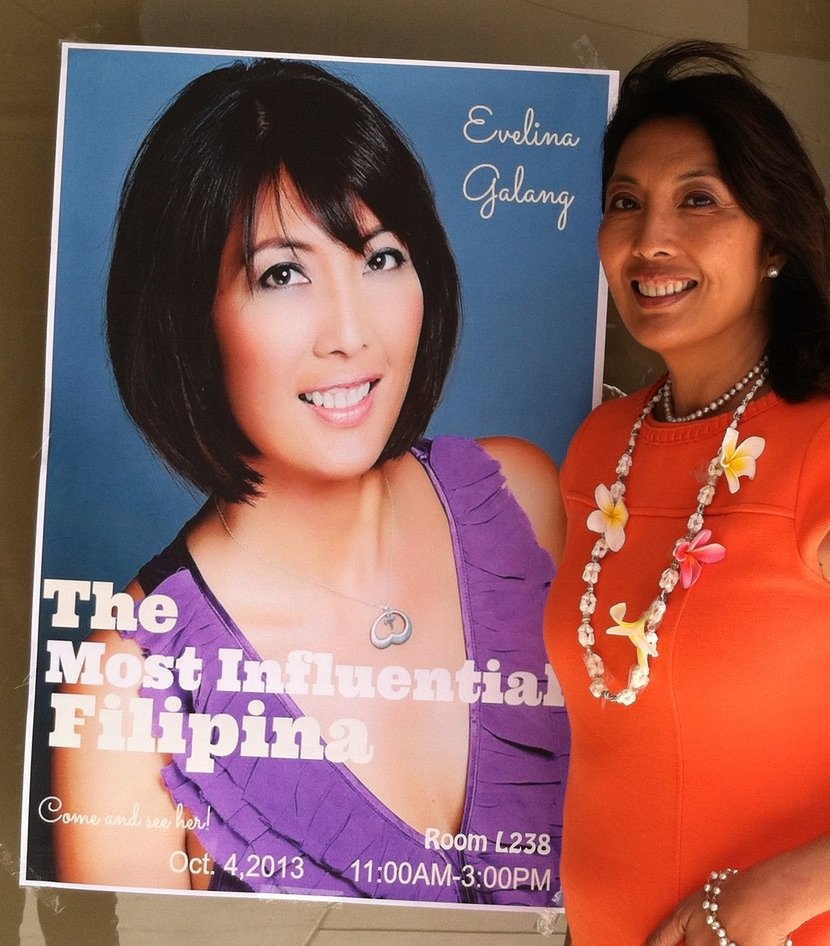

M. Evelina Galang is the daughter of Filipino American immigrants who first came to the United States in the mid-1950’s. Born in Harrisburg, PA, she is the eldest of six. By the time she was twelve, she had moved to seven cities before her family settled in Brookfield, Wisconsin. The author of two novels, two story collections, a work of nonfiction, and editor of Screaming Monkeys: Critiques of Asian American Images, she draws from the stories she grew up on, the research from a Fulbright Senior Research Fellowship, as well as numerous grants and fellowships from the University of Miami. Galang has been recognized as a Dayton Literary Peace Prize finalist, a Cornell Zalaznick Distinguished Visiting Writer, and an awardee of the Gustavus Myers Outstanding Book for the Advancement in Human Rights. The American Library Association named Galang’s Angel de la Luna and the Fifth Glorious Mystery among the recommended books of Feminist Literature for ages zero to eighteen. She lives in Miami where she teaches creative writing.

For an alternative shorter bio, as well as author photos and book images for download, please visit the Press Kit page.

GALANG

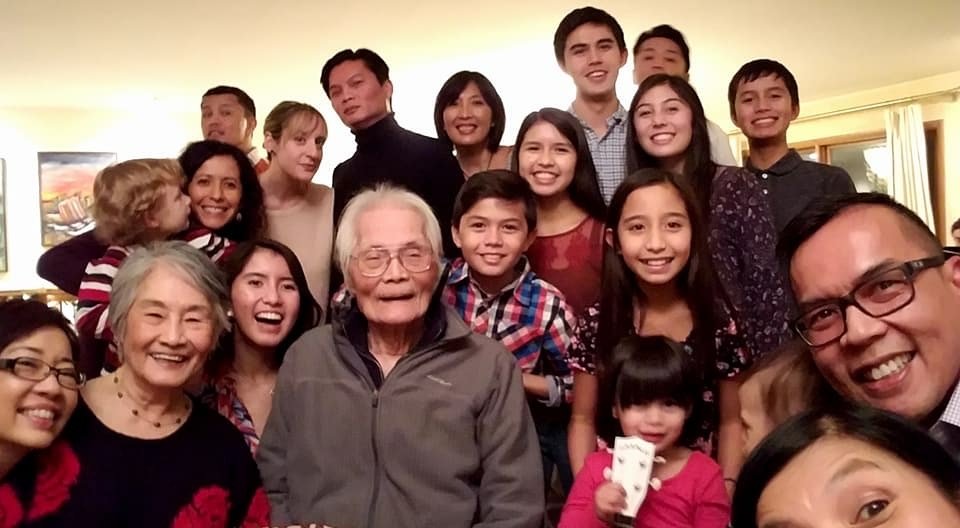

I am daughter, sister, cousin, auntie, wife, Madrastra, and now lola.

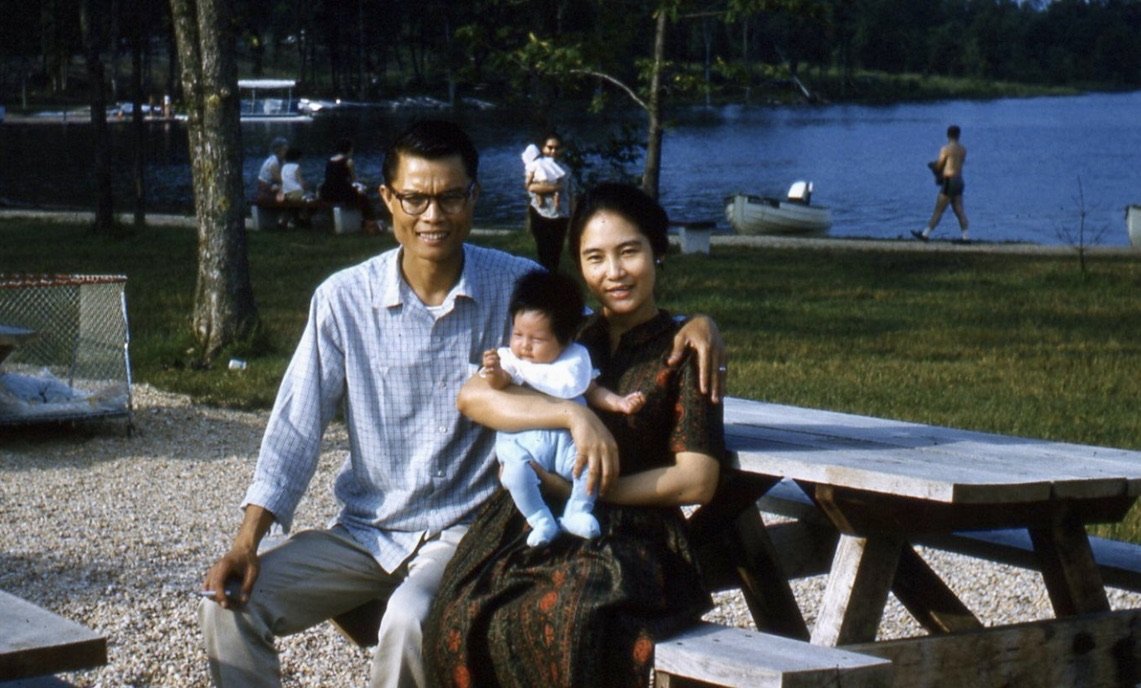

I am the daughter of Miguel and Gloria Galang, Filipino Americans who immigrated to the United States in the 1950’s. They attended the University of Santo Tomas in the Philippines, but never met until one hot August afternoon on the campus of Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. They came here for the opportunity to learn—he, to develop his acumen in medicine and eventually specialize in internal medicine—and she to earn a graduate degree in English literature. I am a product of their love and our last name in Tagalog means “respect.”

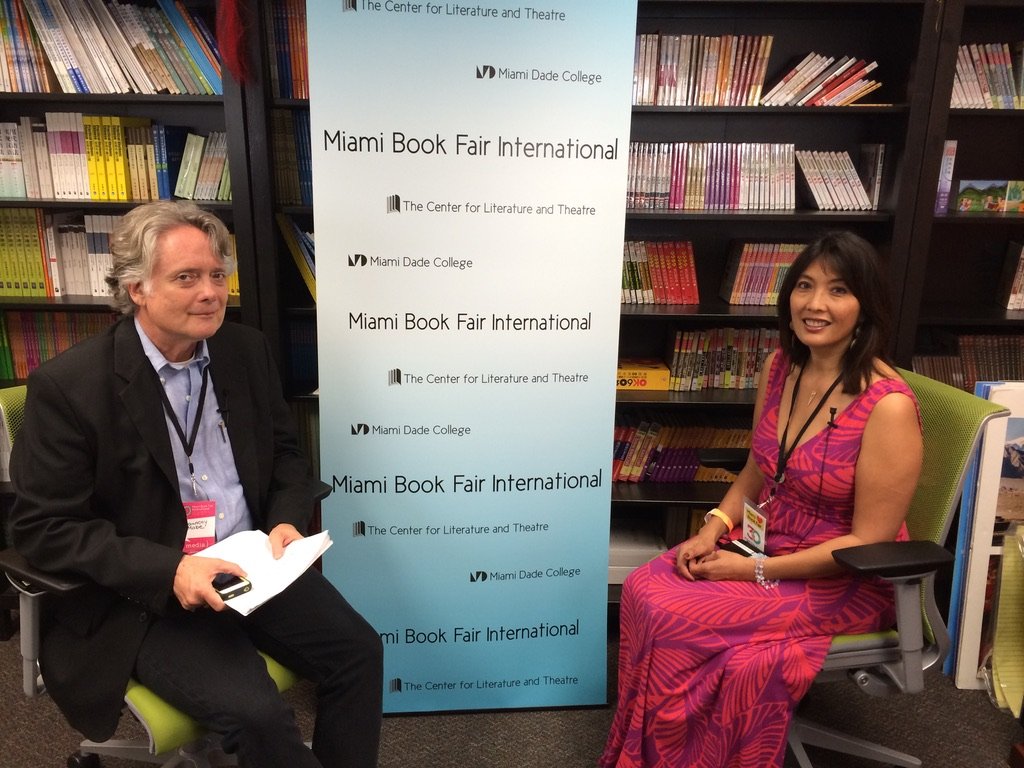

I am the wife of Chauncey Eugene Mabe, a book critic and reporter, a Southern White Gentleman. We met in our fifties. By that time, all my aunties had given up hope of seeing me married. It’s not that I didn’t want to be married, but I was distracted by books.

And though I had met many a handsome and charming man, none of them were my husband. None of them were Chauncey Mabe. We are partners in life in ways I never knew were possible. Our last name, Mabe, comes from the Latin “amabilis” or loveable.

If you try to decipher “amabilis” the Filipino way, you might get “love fast.” But we met late in life, and it wasn’t so much fast love as it was something we recognized soon after our first lunch (which lasted three quick hours).

Before being a writer, an activist, a professor, a mentor, and a director of creative writing, I am a daughter, a sister, a cousin, an auntie, a wife, a stepmom, and now a lola. I am a feminist Pinay, grateful to have the opportunities to create this life.

Mentor

There are multiple bodies of literature being written by writers from all backgrounds…

They are born of our plurality of perspectives…

When I began writing, the only role models I had were the books written by the traditional white writer. These were the books assigned in school, these were the writers who invited me to write—O’Connor, Carver, Munro, Hemingway, Fitzgerald. These writers were my first writing teachers. I didn’t know what it would mean to me to read the likes of Hong Kingston, Morrison, Rosca, Allende, Bulosan, Anaya, Galeano and Walker. I didn’t know the shape of a story could take on multiple forms. That our cultural practices of storytelling could be integrated into the writing of literary fiction.

And then I went to MFA school and wrote my thesis, Her Wild American Self (Coffee House Press, 1996), stories of midwestern born Filipina Americans.

In 2002, I began teaching at the University of Miami, a multilingual campus with a diverse student body.

Then, in 2008, I began working with Voices of Our Nations Art Foundation (VONA) where the mission of the program is to support emerging BIPOC writers with mentors, publishing writers of color like myself.

There are multiple bodies of literature being written by writers from all backgrounds, and from these literatures I cull books to share with my students. They are born of our plurality of perspectives, our nations, our racial, gender and ethnic backstories. There are many ways of writing story. And, through my own practices of writing in English and weaving my character’s natural voices throughout, in their use of Tagalog, or Spanish, or Kapampangan, I have come to teach the practice of multilingual writing in my creative writing workshops.

WritER

Now is the time to be the witness.

To document our experiences through language, image, song.

When I scan the pages of my books, my stories, and my hand-written journals, I hear the voices of the girls and women who have been traditionally silenced. I didn’t mean to choose these girls, these dalagas, these women and lolas to inhabit my stories, but when I look, there they are.

Perhaps I’ve been looking for them in other books, but never finding them, have invited them to come forward in my fiction. Or perhaps it has to do with being born into a community that is constantly speaking and never listening. Who’s going to hear you in all that chaos?

As a teen, I would scribble passionate heavy-inked pages in diaries, hiding my words, but expressing them nonetheless. Writing it down for no one to read was, at first, almost as good as saying it.

These days, as I listen to the noise of white supremacists, bigots, and homophobic sexists, I have felt so heartbroken. What is happening?

I have had the urge to go silent. Only after sitting with this anxiety do I realize the answer is in the art. Is in the story. In the essay. The way to ground ourselves is to sort through the confusion. We cannot be silenced. Now is the time to be the witness. To document our experiences through language, image, song.

These days, I am writing to break through the noise. I will not be silenced.

Community

I would be nowhere without my community

Writing is a solitary act.

I come from a big noisy family, I live among many communities, I love hanging with my friends and feeding them scrumptious meals.

But in the end, when I write, I go off on my own. I quiet my mind and I sit. That is how the writing, the rewriting, and rearranging of story parts happens. All by myself.

And yet, I would be nowhere without my community.

The people in my communities come from all walks of life. I sit among them. I listen. I breathe. I take note. I rest.

When we are gathered at a table with food before us, we feed more than our bodies. Community supports me. Community encourages me.

Community tells it like it is and sometimes the words are hard to hear. Sometimes all we do is laugh. And of course, there are times when there is crying. If you read the acknowledgments of any of my books, you’ll see. I have so many people to thank for putting up with me, reading me, giving me feedback, reading me again. For allowing me to read them, learn from them, go back and write.

Often it is my students who teach me the art of writing a good story in their fresh, irreverent ways, through the lens of their world and in their dedication to literature.